Traditional Chinese New Year celebrations present a lot of surprises to the non Chinese among us. Words by Beverley Ann D’Cruz

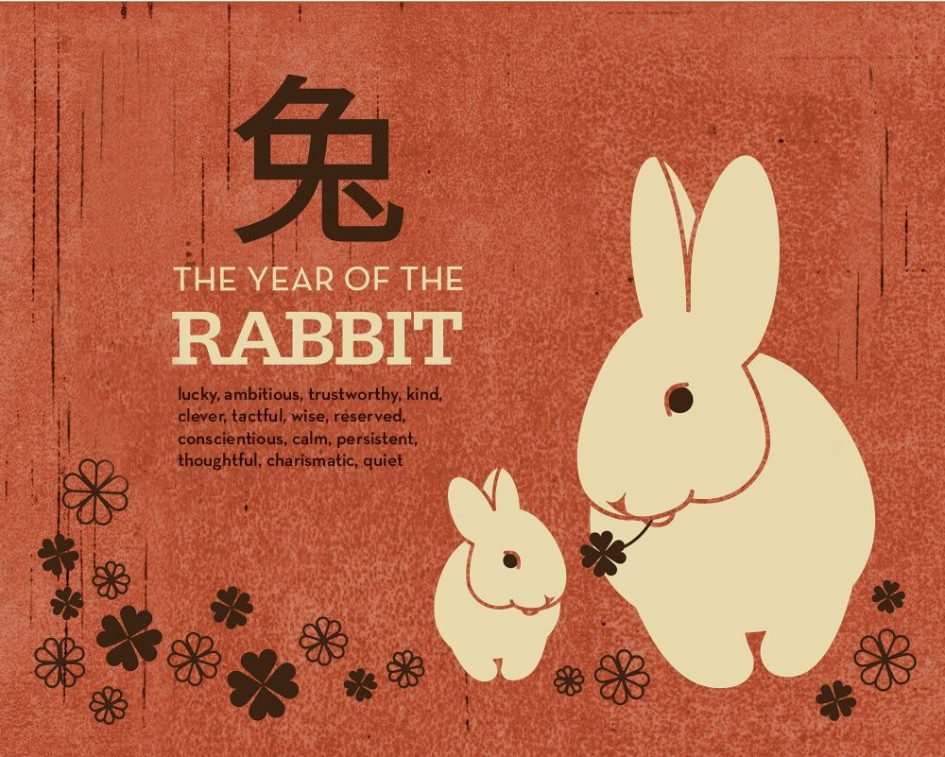

When February blows in this year, many people will have forgotten their New Year’s resolutions. But while 2011 loses its fresh charm, the Chinese community in Mississauga will be preparing for the auspicious occasion of their New Year falling on February 3rd and will kick off the Year of the Rabbit.

Considered their most important holiday, the festival is dictated by the Chinese lunisolar calendar and generally coincides with the second new moon that occurs after the winter solstice.

I find a stronger sense of celebration seems to come from the community

In China and Hong Kong, schools and businesses are closed for seven days allowing families enough time to reunite and celebrate together. However, here in Canada there are no holidays dedicated to the festival. So residents like Josephine Bau, the Chinese Community Advisory Council Chair for United Way of Peel Region prefer to ring in the New Year on the weekend closest to the day.

“Sometimes we can take time off but that doesn’t necessarily mean the rest of your family can do the same,” explains Bau, who originally hails from Hong Kong. “I find a stronger sense of celebration seems to come from the community. At Mississauga City Hall they host a reception on the first day of the Chinese New Year and host the traditional lion and dragon dances as well. Other community organizations organize performances and dinners so there is a lot to look forward to.”

Each day of the traditional festival carries a special significance and differs for each family depending on their region of origin. Day one is when the gods are welcomed into the home and people abstain from meat hoping this sacrifice will ensure long life and happiness. Day two is reserved for prayers to the gods and ancestors, days three and four are for husbands to pay respect to their in-laws. On po woo (the fifth day) no visits are made to friends and family (as it is considered bad luck) and instead people stay at home to welcome the god of wealth. From the sixth to the 10th day people visit the temple and homes of close relatives and friends. “As a sign of respect for seniors, young people are expected to visit the homes of their parents and older siblings,” adds Bau.

The festivities culminate on the fifteenth day with the lantern festival and the preceding day is used to make preparations. Before the big feast on New Year’s Eve, care is taken to clean houses and sweep away any bad luck. Homes are sometimes repainted, new clothes and presents are bought and houses are strung with lanterns and paper decorations. Doors are decorated with the fortune sign above them and paintings of poetic spring couplets and New Year’s wishes are hung on the sides.

Feast day dining tables are laden with delicacies like noodles, which are served uncut to symbolize longevity; salt-baked chicken served along with its feet and head to indicate completeness; seafood like clams and scallops as their rounded shape is similar to that of coins and represents good wealth and fortune; and oysters and lettuce that indicate good fortune and prosperity. Fish is a must on the table as it represents surplus and is something that is hoped for in the New Year.

“On the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, every door in the house, and even windows, have to be open to allow the old year to go out,” says Lillian Kwok, Vice President, Mississauga Chinese Business Association.

Another tradition looked forward to, is watching special New Year’s programming on the Chinese television networks. Families gather together to enjoy performances by famous singers and movie stars on New Year’s Eve and the following day. In fact, these programs are so popular that Chinese immigrants will ask friends to record it if their family misses the dedicated telecast so they can watch it together later.

Although celebrations may differ in each household in Mississauga, most families share the wish for good health, luck, happiness and a prosperous year. Explains Kwok: “While many Chinese people today may not believe in these dos and don’ts, these traditions and customs are still practised… because most families realize that it is these very traditions, whether believed or not, that provide continuity with the past and provide the family with an identity.”